Feeding The World | How the protein transition might surprise all

Changing consumer behavior will not save our planet. Technology will.

👋 Hi, it’s Michiel, back to writing after a long summer break.

We took our campervan for a long holiday in Northern Spain, from the Costa da Morte (North-West) to the Pyrenees. 10/10 would recommend.

So now I’m rejuvenated and thrilled to spend my time again on Sustainable Growth:)

I’d like to start with a warm welcome to Maximilian, Belle, Gloria, Dave and 20 new subscribers who joined Sustainable Growth. It’s a pleasure to have you here!

I thought: ‘Why not start with some hopium?”

So today, I am taking a closer look at the industry that feeds the world:

Food & Agriculture

For centuries this industry has been at the center of our societies.

Today, it still is the biggest and most important industry known to mankind. Except perhaps from the financial perspective, it plays a relatively small role in our world economy (8% of global GDP) compared to the actual role it plays in the tangible world.

Some examples:

- 855 million people are employed in the food and agriculture industry (20-25% of global jobs)

- 50% of the ice- and desertfree land is used for growing crops and livestock.

- 31% of global emissions are directly related to feeding ourselves.

Let these sink in for a minute.

Many jobs at stake

The amount of jobs in this industry is enormous. Comparable to all manufacturing/industrial jobs and about half of all the jobs in ‘Services’.

This means Agriculture still has very strong ties to most communities and major shifts in this industry will therefor always invoke political activity or instability. Especially so, when changes are forced by governments or law, instead of their markets (technology, consumer demand, competition, etc).

That’s a lot of land

50% of all land that is not a desert or covered with ice. That is the size of the combined Americas, from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego. Just to grow crops and keep livestock. For comparison: our villages, cities and infrastructure make up for 4% of global land use, where densely populated regions see up to 15% of land being build upon.

Our food has major impact on climate change

31% of emissions are related to our own food. Reaching our global climate goals will prove impossible without this industry reinventing itself or its resources. It is very capable of doing so, since farmers have been the first to experience the changing climate and are forced to respond, change and innovate across the globe. On a local level this means growing different crops and using new methods. On a global level the major shift is expected to come from the ‘Protein Transition’; the plantification of our diet.

You are what you eat, but what do you need?

2.960 calories per day. That is the global average daily caloric intake of an adult. This varies per region, between body types and between sexes. For the sake of simplicity, let’s stick with this ‘dumb’ average.

Depending on your age, fitness and level of exercise you want between 10% and 35% of those calories to be from proteins.

A young adult, having a dull day at the office, without any exercise, needs only 200 calories from protein, which is equal to 50 grams of protein. Where a more senior adult (58 years) that does weightlifting and substantial training for a marathon, might need around 1.100 calories from protein (225 grams) that day.

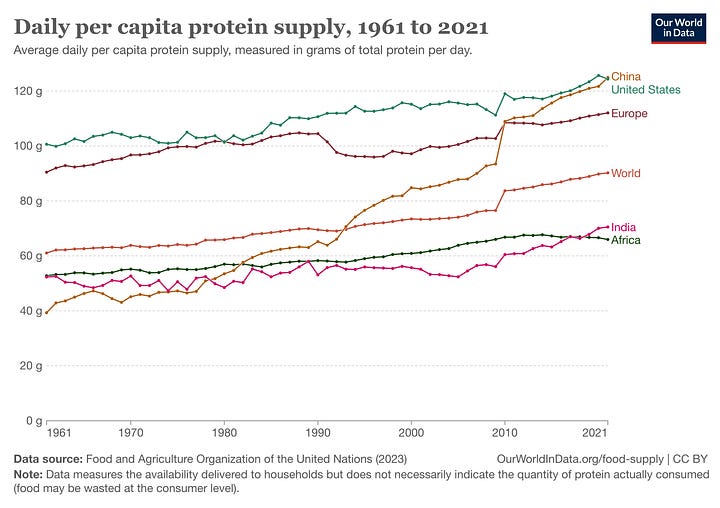

The daily average intake of protein is rising. Adding up to 30kg of protein per person a year. This is what we actually eat, the ‘healthy’ average would be closer to 25kg a year.

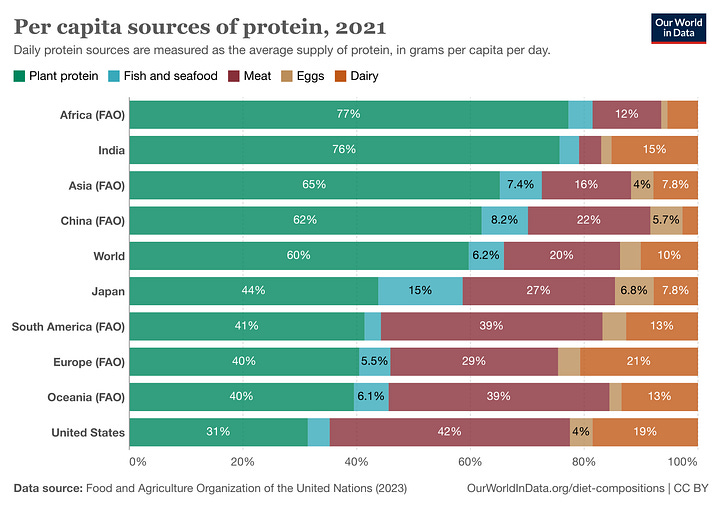

What type of protein you’re getting depends largely of the combination of your income and regional availability. Higher incomes tend to increase their protein intake from meat and/or dairy.

So, how does our protein intake affect the world around us?

Climate Impact

I’m sure none of this is new to you. There’s plenty of relevant topics when considering the climate impact from livestock and growing crops. Greenhouse emissions, loss of biodiversity, soil depletion, soil pollution and water pollution to name a few. All of them impactful and worrisome in their own right and any investor or entrepreneur active or interested in this industry should comprehend each. For this piece however, I’ll focus on emissions and land use, because those are tied to livestock.

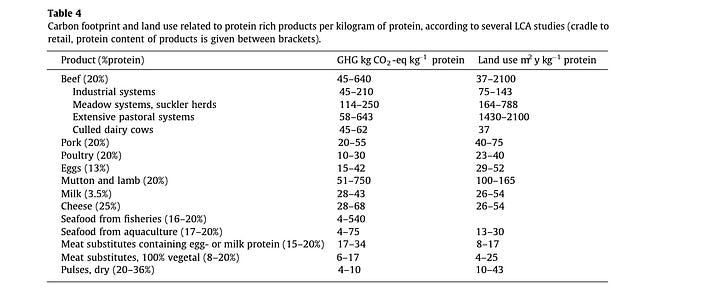

Looking at these graphs it’s clear that when we’re eating beef, mutton or lamb, we have a profound negative impact on our emissions. Cows and sheep are inefficient ‘gainers’, who need a lot of food for a little bit of weight and they produce methane in the process. Methane being one of the hardest punching greenhouse gasses out there.

Diets weigh in heavily - a comparison

An athlete with a high protein diet comprised mostly of beef, chicken and eggs will emit around 15 tonnes of CO2-equivalent per year. Someone with a locally sourced vegan diet will emit between 0,5 and 1 tonnes of CO2-equivalent. Just from what they’re putting into their mouth.

To put that into perspective, the average global emissions per person are around 4,6 tonnes, with the European average hovering around 7,5 tonnes and the average in the USA around 16 tonnes per person.

Land Use

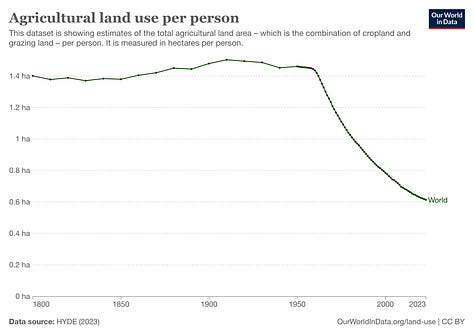

In the first edition of Sustainable Growth, my mission statement if you will, I’ve highlighted Population Growth as ‘The Ugly’ force at play in the near future as it will put a lot of pressure on our ability to farm enough food and build enough houses. For which we need more habitable land.

Our boom in population is hardly a new phenomenon, hence we’ve destroyed so much of the natural world in the past 120 years, just to be able to meet these demands. Not pointing fingers here, it happened.

The invention of industrial fertilizer, by Haber and Bosch, is estimated to support around 50% of today’s world population. Together with improvements of the nutritional quality of our grains and improved storage, this means we’re now feeding 4 times the population on 1,8 times the cropland compared to 1900. Talking about achievements. That is impressive.

The use of land for livestock has more than doubled. The size of our herds tripled, since they also benefit from fertilizer and crop improvements.

Resulting in a world where humans and ‘our’ animals make up 98% of the mammals on earth.

The graph above tells us about diets on a global scale, with a 75% decrease in land use between current global diet and a vegan diet.

If we compare the athlete and the vegan diet again, the difference is far greater.

The protein-rich athlete might use up to 7 whole football pitches a year and the locally sourced vegan will live of just one penaltybox.

So, how about your individual land use?

Are you destroying our world, one bite at a time?

Should you be posting AITA-confessions on Reddit?

Habits eat Logic for breakfast

Until recently, these facts where regularly accompanied by a moral obligation to change your behavior. As if it was a clear right/wrong story and we could just persuade others by pointing at the inherent logic.

I’ve worked long enough in marketing to know that logic isn’t the magic wand to convince others. Appeals to status, sense of belonging, social proof, joy, creativity and habits are better tools in most cases.

Doing the right thing sounds easy, but it is incredibly hard. Certainly when it means you’ll have to change one of your core habits. Certainly when it means changing a habit with cultural significance, that you’re sharing with other people. Don’t underestimate how important of a habit our food is.

Some introspection: I let very few people tell me what to eat and even fewer how to cook.

So it comes at no surprise to me that the amount of vegans has only slowly grown past decades. I applaud each of them for their grit and perseverance.

And I’m happy we’re now at a stage that we can avoid further blaming and shaming. A disruptive wave is about to hit this industry.

Plant-based meat and dairy alternatives are gaining momentum

The past decade we’ve been introduced to ‘new’ plant-based protein by successful startups like Beyond Meat, Eat Just, Oatly and Alpro to name a few. These frontrunners seem to focus on shifting demands from customers: selling new products to climate-aware consumers at a premium.

Yet, many of these products are not intended to change our diets and eating habits. On the contrary. They’re just replacing what we’re used to, with a plant-based or bacteria-based alternative. Which means they’re not arguing with us logically. They’re trying to make their products blend in. Taste, smell, texture and even proporties like ‘stretch’, ‘marbling’ and ‘melting’ are developed to make sure we won’t notice any difference.

To do so, a range of technologies is developed and though many are still in infancy, we’re now seeing them break trough to the general public. And they’re becoming affordable.

In 2022, plant-based meat substitutes and plant-based dairy substitutes were between 50% and 65% more expensive than their animal-based counterparts. And these higher prices are very sensible, since developing new technologies and scaling up are very costly for any business.

This year, it’s expected that the majority of the plant-based alternatives will have a lower production price per product than the animal-based products. That will allow these companies to start dropping their prices and reach price parity with the animal-based alternatives.

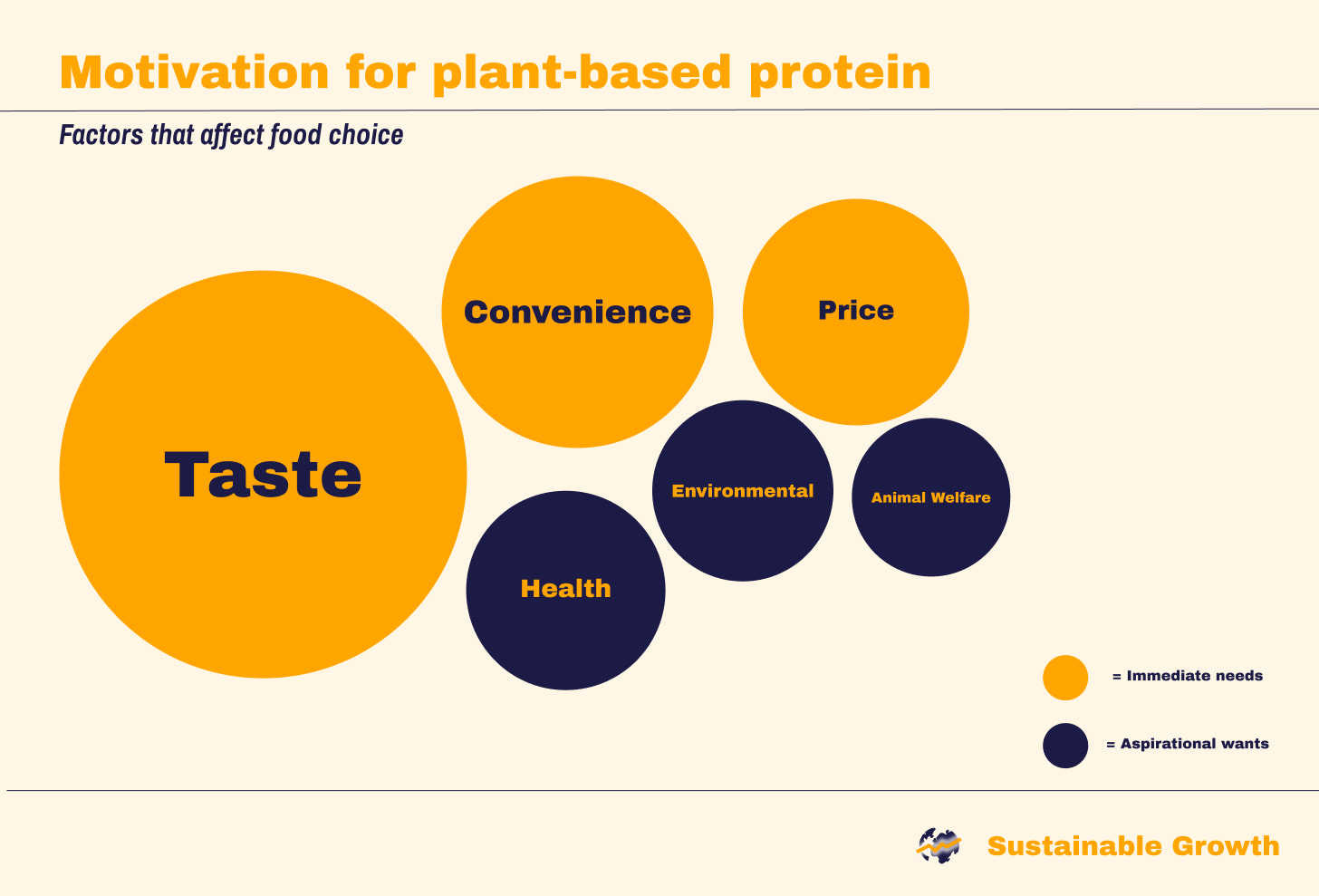

Studies show that consumers do think about where they’re going to buy their food, in order to maximize several ‘aspirational wants’, like looking for health benefits, reducing environmental impact and concerns about animal welfare. However, when deciding what to buy, three major factors come in to play. These ‘immediate needs’ are taste, convenience and price.

Recently, many plant-based products are passing the taste test. Flavor and texture have improved significantly. While reaching price parity these products will be introduced to a vastly bigger audience. Making them more convenient in the process.

During 2024 and 2025, many plant-based alternatives will reach the general public at acceptable pricing, widely available and with good taste.

Are we looking at steady growth or a tipping point towards disruption?

Financial analysts seem to agree on the fact that plant-based meat and dairy are mere additions to the meat and dairy categories. Growing steadily as long as consumer demands evolves.

To give you some examples:

- Global agriculture revenue is around 4 trillion, with an expected compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3,5% towards 2030.

- Global food processing industry revenue is around 4 trillion, with an expected CAGR of 3% towards 2030.

- Global food and beverages retail industry revenue is above 11 trillion, with an expected CAGR of 3,2% towards 2030.

- Global plant-based meat and dairy revenue is 0,0018 trillion, with an expected CAGR of 10% towards 2030. Some even consider 15% CAGR to be more realistic.

From a investment perspective it’s clear that ‘plantification’ has a lot going for it.

Tipping point in sight

However, I believe they’re wrong and way to conservative, as I think they’re completely oblivious to what is under the hood. Plant-based is treated as addition, but it will replace the majority of the meat and dairy categories.

I would like to compare it to the introduction of the car. At first, an expensive new technology, prone to break along your trip. For many it was a vanity item.

Horses were the reliable, available, socially acceptable and cheaper option to get from A to B. Until the car became reliable, available, socially acceptable and cheap. It took two decades for the car to get through infancy (and reach 2% market share), it took one subsequent decade to reach 60% of market share (the obsolete horses flooded the meat markets as a result).

Here’s why I compare these:

Capacity to innovate

Capacity to reduce costs

Land value vs. insecurity of business operations for livestock

Capacity to innovate

The meatless burger and a beef burger share quite some resources: crops, water and energy. To improve the beef burger means we’re looking at improving the growth of the animal (growth efficiency, protein, quality, fat, etc.). Some of that can be accelerated by lab-work and crop improvement, but it still means the animal has to grow. To improve a meatless burger means we’re looking at improving crops, extraction technology, production technology and discovering new methods entirely. The possibilities for innovation are far greater with the new plant-based, bacteria-based and fungi-based alternatives. And they’ll be able to innovate at a higher pace.

Capacity to reduce cost

Livestock farming is close to its maximum efficiency. Increasing herd sizes is expensive and introduces rising costs to surpress health risks. Meat and dairy can become cheaper if crop prices, energy prices and water prices drop. But that’s hardly a competitive advantage, since plant-based production will equally benefit from these lower prices. The 450+ companies that are producing plant-based meat and dairy still have a lot of room to upscale their operations and production, with inherent efficiency gains. Even in a scenario where no further innovation happens, scaling up production might see plant-based alternatives reach a price of 40% of the animal-based original.

Land value vs. insecurity of business operations with livestock

In the past three decades a real ‘land squeeze’ has taken place across the world because of rising land prices. In most nations the top 1% of farmers hold more than 50% of the farmland. Small and medium sized livestock farmers have struggled to make a living and sold their lands to bigger competitors or repurposed lands for solar energy, recreational use or residential development. This trend will only accelerate, since only those with deep pockets are able to enter and grow in the market. If land value keeps rising further, at one point the opportunity cost of livestock will become negative for even the biggest farmers, certainly if they’re forced to respond to the pricing pressure from the plant-based competition that is about to develop. Many entrepreneurs and investors will try to reduce their exposure to these risks before these actually unfold. Until now, the’ve had little to fear from plant-based competition, since it was priced at a premium.

Meat farmers were competing with meat farmers. I expect them to accept their new competition during 2025.

Meat and dairy farmers might decide to grow crops on all of their arable land, or even sell their lands. The supply of meat and dairy might drop, increasing prices if demand is not dropping in the same rate. Further speeding up the flywheel of ‘plantification’ in the process.

Meat and dairy from animals will stay part of our diet. I’m convinced that the cultural significance and dominance in our gastronomical industry will keep generating considerable demand. But I can’t see why 60% - 90% of our intake couldn’t be replaced by alternatives. I wouldn’t be surprised if the whole animal-based meat and dairy industry goes through a thorough rebranding to ‘artisanal’ across the isle and see itself become a niche category for a premium.

Put your money where your mouth is?

The 10% - 14% CAGR range that analysts predict is on the lower side of what I suspect will happen. I wouldn’t be surprised to see plant-based protein do much better once its prices are on par with the alternatives. I suspect we might even see 20% CAGR until 2030. In any circumstance the growth is way better than the overall food market.

A €100 investment made today (2024), will yield these values in 2030:

- €127,22 if invested in the industry at large

- €194,87 - €250,22 if invested in the plant-based meat and dairy industry (according to current analyst projections)

- €350+ if invested in these plant-based producers and if they prove to be a disruptive force.

The result: decreased scarcity of habitable land.

There are two types of land where cattle and sheep are held. Arable land, which we can plow, and marginal land, which is unsuitable for growing crops.

In a scenario where the demand for cattle and sheep would disappear between 10-25% of the land that becomes available would be arable land, suited for growing crops. In some cases those lands need grazing and menure to rejuvenate the depleted soil. Cows and sheep eat a combination of grass, crop waste and crops. About 20% of their diet consists of human-diet crops.

We can expect that livestock farming will stay a part of the exploitation of the marginal lands. Yet, some of these lands are also suitable for energy production, water storage or recreational development. And almost all of these marginal lands can become part of rewilding projects, increasing our CO2 storage in nature.

To feed a growing world population we will see a rise in demand for crops. Though the demand from the plant-based meat and dairy industry might replace the demand from the current livestock. We can expect that a fair share of the arable land in said scenario will be used for extra crops. By doing so we’re able to further reduce food prices if we manage to curb soil depletion.

We can expect that a fair share of the arable land will become available for energy-, recreational-, infrastructure- and residential development. Some quick on-the-back-of-the-envelope math: this can roughly double the land used for these purposes (from 4% now, to 8% in the future). If such a thing happens in a short period of time, land prices would fall considerably in some parts of the world.

Not everywhere though. Climate change will force humanity to live in ever denser cities in those locations that are least impacted by it and it will force us to move to rural areas that until recently were unhabitable.

Conclusion

We’re building to little, to expensive to provide housing for all and we’re competing for land with the animals we’re eating. Destroying the natural world in the process. We’ve been ‘wanting’ to change this for quite a while by changing what we eat, but we did not manage.

Until now. We can eat better, without eating different.

Technology will disrupt the way we grow and eat our protein.

Unblocking us in other areas.

What do you think?

Do you agree, are we going to witness a disruption?

Or is this to much hopium for your taste?

Let me know!

Help the newsletter reach new readers and share this post with others. Thanks:)

No sorry , I have purchased the new artificially coloured and flavoured , plant based meats when they are on throw out prices and still determined never to go back. Many of the flavour of the month businesses have burnt millions and failed . I can’t see this turning in under a generation. You need to breed a generation who don’t know the taste and sensation of a steak with prawns to turn back that dial. Thankfully the beef cattle on well maintained pasture don’t have a great contribution to co2 so that will help your graphs a little.